Chatper 3.3 - Dive into Application Details

Application Details

Absolutely, further insights are crucial when it comes to understanding both the characteristics and interconnections of applications. Given their complexity, applications can be depicted from multiple angles. We will delve into:

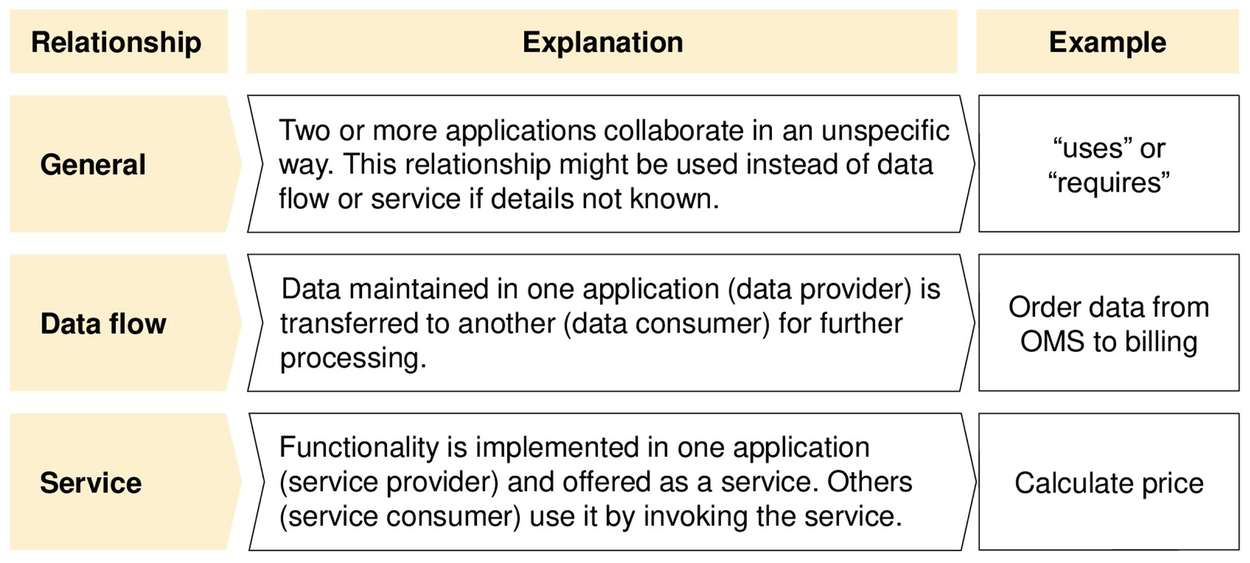

- Inter-Application Relationships: This section will explore the intricate web of connections that exist between different applications, highlighting how they interact and depend on one another.

- Application Management Properties: Here, we’ll outline the key attributes that are essential for effective management of applications, detailing the various aspects that need to be considered.

Application Interaction and Services

Understanding Application Relationships

Applications in a business setting do not exist in isolation; their strength lies in interconnectivity. For instance, a typical business process is likely supported by multiple applications that seamlessly exchange data. Imagine the interaction where Salesforce.com shares customer account details with both a transport management system and a ticketing system. This exchange is crucial for operational harmony.

The Evolution of Architecture

In the realm of enterprise architecture, there has been a significant shift from service-oriented architectures (SOA) to the current trend of microservices. Despite this evolution, the essence of providing services remains a cornerstone in modern application landscapes. Services are essentially functions offered by one application for use by others, akin to function calls in programming languages, complete with input and output parameters.

Data Flow and Service Utilization

Take, for example, the flow of order data from an order management system to a billing system for invoicing purposes. This is a data flow that is replicated across various business objects and processes. Services can be crafted not only for data exchange but also to encapsulate reusable functionality, such as a price calculation service that is used across customer offers, order processing, and invoicing.

Early-Stage Relationship Mapping

In the initial stages of mapping an application landscape, details about whether interactions are service-based or data flows might be unclear. However, documenting these general relationships is vital for understanding the interplay between different systems.

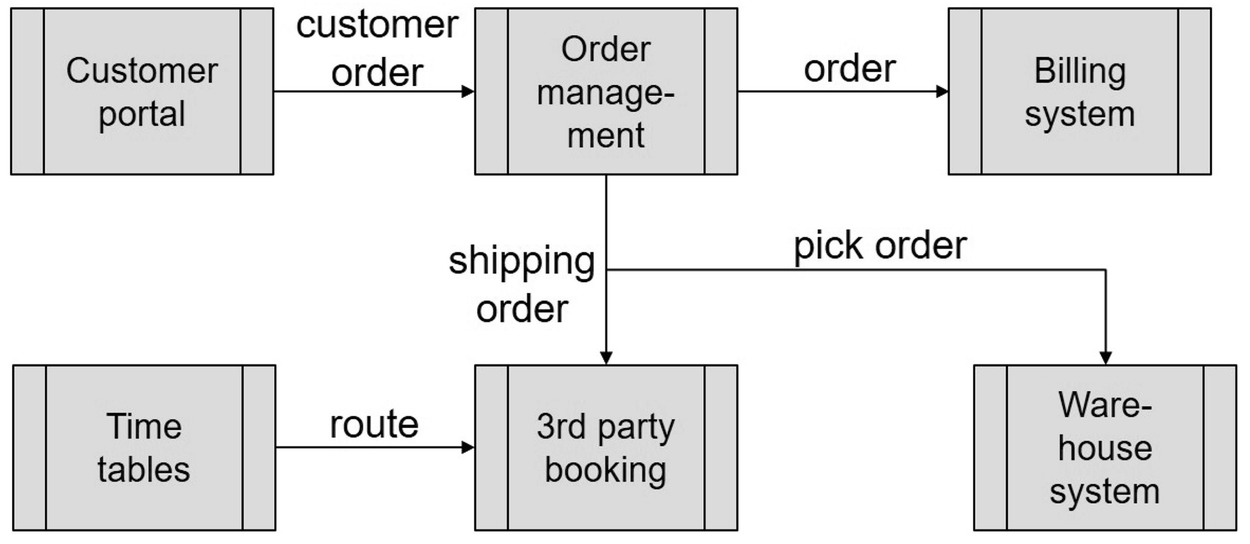

Visualizing Data Flows

The visualization of data flows, as shown in an example application landscape, is a powerful tool used by many organizations. It simplifies the understanding of application interactions, which is foundational for integrating e-commerce processes and supply chain management. Even though the example is simplified, real-world company maps can involve hundreds or thousands of applications.

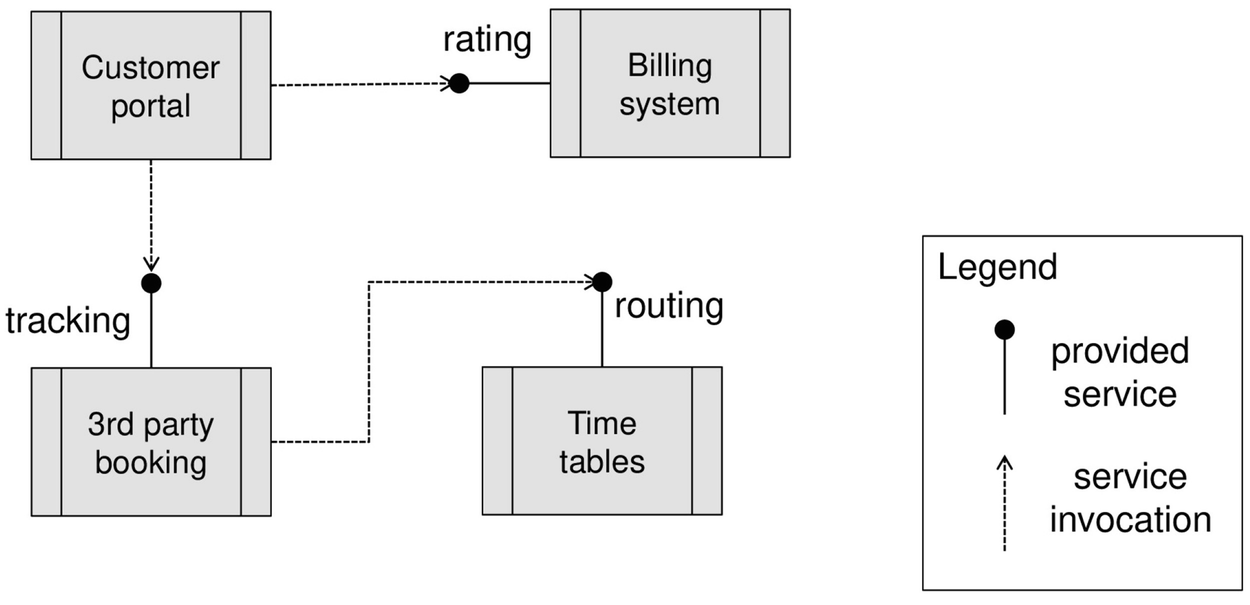

Service Provisioning in Practice

To illustrate service provisioning, consider a billing system that offers a rating service. This service, used to calculate product prices, can be invoked by various applications like a customer portal, thereby centralizing and streamlining the pricing functionality.

Economies of Scale Through Services

The development of services like tracking in a third-party booking system or routing in a timetable system exemplifies the economies of scale achieved through service-oriented architectures. These services provide specialized functionality — tracking the status of shipments or calculating optimal shipment routes — that can be leveraged across multiple systems, avoiding redundant implementations.

In summary, the interconnectedness of applications through services and data flows forms the backbone of efficient and scalable enterprise architectures, enabling organizations to optimize operations and foster innovation.

Essential Information for Application Landscape Evaluation

In evaluating the application landscape, a detailed understanding of certain information is pivotal for two main scenarios:

Current State Analysis (As-Is)

- Purpose: To grasp the existing application environment.

- Data Needed: Information that pinpoints and documents present challenges, serving as a basis for landscape optimization.

Future State Planning (To-Be)

- Purpose: To outline the envisioned future of the application landscape.

- Necessities: Criteria for benchmarking the current landscape against the future one.

Relevant Data Types

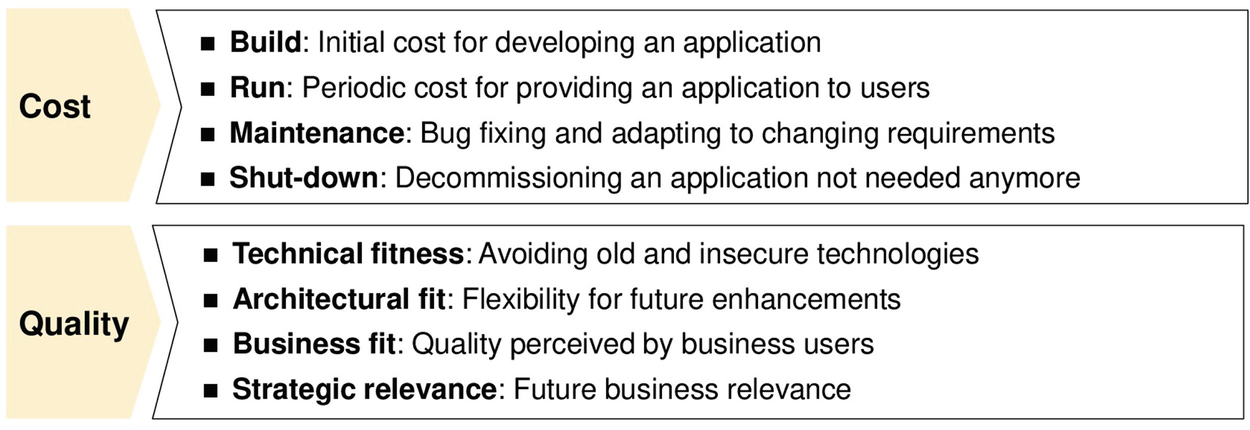

As shown in Figure below, the analysis of the application landscape revolves around two primary data types:

Cost Information:

- Coverage: Initial and recurring fixed costs for setup and provisioning, alongside variable maintenance expenses for updates and bug fixes.

- Significance: Section 1.1 (illustrated in Figure 1.6) emphasizes cost concerns, particularly when dealing with a sprawling, unchecked application landscape.

- Impact: Identifying and consolidating redundant applications to reduce both numbers and complexity is a key focus.

Quality Assessment:

- Considerations include:

- Technical Implementation Platform: Outdated environments may drive up future maintenance costs. It’s often advised to phase out legacy systems.

- Architectural Fit: The degree to which applications adhere to organizational principles and align with business processes.

- Data Exchange Capability: The need for dedicated translation systems indicates architectural mismatches, potentially disrupting data flow.

- Business Support: Applications must fully enable business capabilities and optimize process execution.

- Strategic Contribution: Prioritization based on how applications support current and future strategic objectives.

- Considerations include:

These factors are crucial for evaluating current applications and the overarching architecture, informing decisions based on quantitative metrics like cost reduction or quality enhancement.

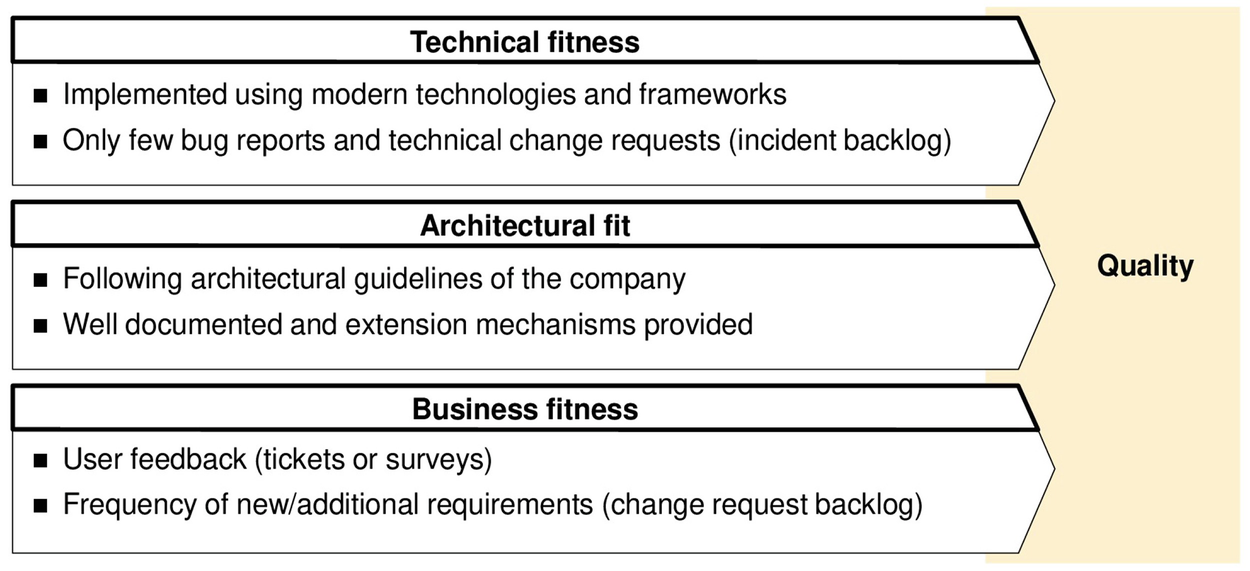

Quality Attributes Detailed

Technical fitness, a component of quality, is assessed based on:

- System Age: Whether the software relies on mainframe technology or modern frameworks.

- Architecture: The system’s holistic architectural adherence and documentation quality.

- Maintainability: Measured by the frequency of bug reports and technical amendments needed.

Architectural fit extends beyond technical implementation to consider integration with other applications and adherence to enterprise architecture (EA) guidelines.

Business fit is gauged through various methods:

- Surveys: Gathering user feedback on application efficacy.

- Ticket Volume: High numbers of user complaints can indicate poor business fit.

- Change Request Frequency: Frequent demands for changes suggest the application may not fully meet current business needs.

In conclusion, an extensive backlog of change requests can signal poor business alignment. Conversely, a popular application may attract numerous enhancement requests.

In essence, understanding the application landscape requires data on individual applications, their interconnections, and user feedback. Although data collection is arduous, it’s a necessary step for informed decision-making and landscape optimization.

Advanced Concepts in Enterprise Architecture

Expanded Application Landscape Elements

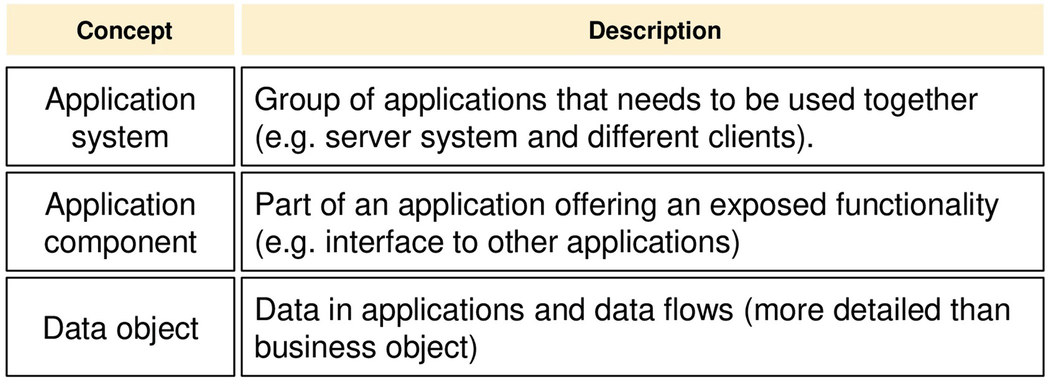

Beyond the foundational aspects of the application landscape, there are several advanced concepts illustrated in Figure below. These are not critical for the rest of this textbook, but it’s important to know about them as some Enterprise Architecture Management (EAM) tools may utilize these concepts:

Application Systems: This term refers to a collection of interconnected applications functioning together as a coherent group. For instance, SAP represents an application system comprising multiple individual applications such as:

- ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning)

- TM (Transportation Management)

- CRM (Customer Relationship Management)

- Plus additional applications

Together, these applications form a comprehensive software system designed to operate in unison.

Application Components: Applications can be dissected into smaller units known as modules or components, offering a more detailed view of the application’s capabilities. For example, a logistics management application might be divided into:

- A planning module for reservations

- A communication module for dispatching bookings to partners

- A monitoring module for overseeing transport operations

In this scenario, the application is segmented into three distinct components, and the presence of interfaces for interaction with other applications might necessitate the creation of specialized components.

Data Objects and Their Role

The concept of data objects is frequently associated with application architecture discussions. Our previous examples in the application landscape have already hinted at the presence of data flows between applications. To accurately describe these flows, the concept of a data object becomes essential.