Chatper 5.1 - Managing Changes of Enterprise Architecture

Managing Changes of Enterprise Architecture

In the realm of Enterprise Architecture (EA), we encounter various types of changes that can impact the business significantly. Below are some common scenarios that exemplify these changes:

- Introduction of new organizational units to support new products or ventures

- Alterations in business processes

- Restructuring of organizational hierarchy

- Reallocation of responsibilities among staff

- Outsourcing or offshoring activities, such as IT services or customer support to regions with lower labor costs

Changes within a business can stem from numerous sources, including shifts in the market, but alterations in applications can also instigate modifications to business processes. It’s a two-way street: business and IT changes influence each other. For instance, an adjustment in the business domain often necessitates multiple updates within the application landscape, and vice versa.

In this book on EAM, while we acknowledge the importance of changes in business practices, our primary focus will be on the changes within the application landscape, their management, and how they align with business processes. These changes might include:

- Deploying a new software application which must be seamlessly integrated with existing processes and systems

- Adapting a system with additional functionalities

- Expanding the use of a current application to additional organizational units

- Decommissioning obsolete applications to cut costs related to hosting, maintenance, and operation

Application Portfolio Management (APM) is the discipline that handles such changes and is intrinsically linked to EAM. Utilizing analyses and visualizations from EAM, APM also connects to financial accounting and project management, overseeing the myriad projects that address these changes. In this chapter, we will examine these changes individually, without delving into their interdependencies.

Navigating Changes in Enterprise Architecture

Change is constant, but in the corporate world, it’s anything but simple, particularly when it involves altering human behavior. Employees are often required to adapt their work habits—practices that were once familiar but may no longer be relevant post-change. Sometimes, even organizational roles undergo transformation, potentially affecting individual salaries, their perceived importance, and self-esteem.

When questioning organizational issues, many will share their perceptions. Similar to a pub discussion on politics, everyone has an opinion on improvements. People may initially support changes to resolve these issues, but enthusiasm often wanes when they must alter their own behavior. Change isn’t just a logical solution to a problem—it’s a personal matter, requiring individuals to let go of trusted habits and beliefs that may have become obsolete. Motivation for change typically diminishes when self-transformation is on the line.

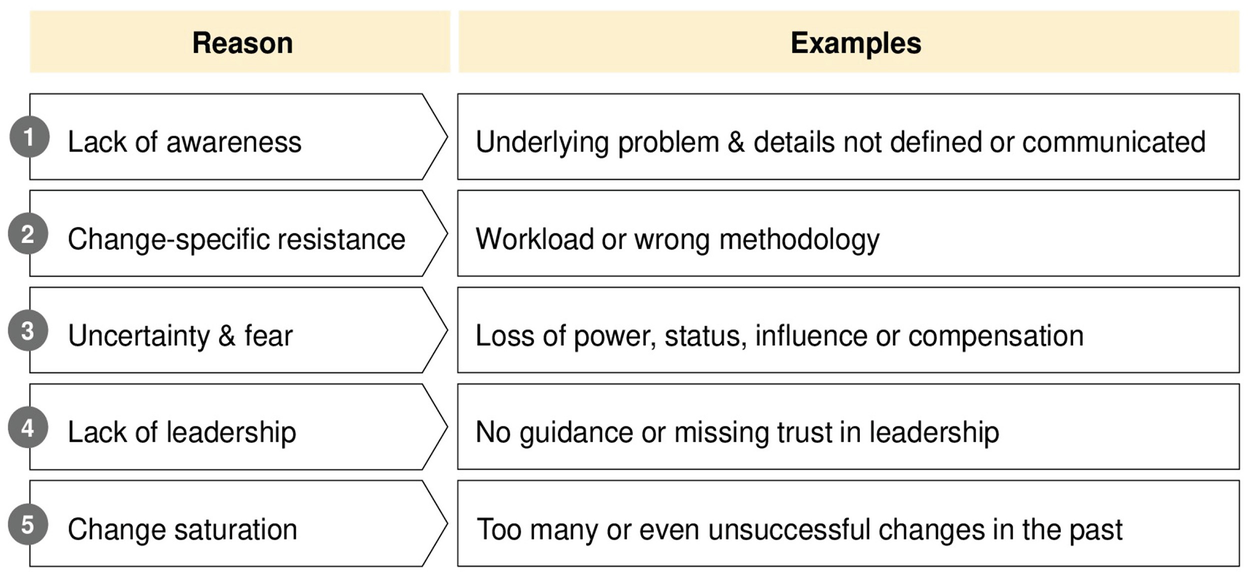

Resistance to change isn’t about making management look bad or avoiding change for the sake of it; it’s driven by concrete reasons. Figure below outlines some common causes of resistance:

Reasons for Resistance to Change

Lack of Awareness: People might not recognize the need for change, finding comfort in the status quo. They may not realize they contribute to or work within the problem, and thus also need to change.

Overwhelmed with Work: Employees already inundated with daily tasks and overtime may feel they can’t allocate time to plan and implement changes, fearing an increased workload.

Emotional Uncertainty: The emotional side of change can be daunting. Concerns about the impact on one’s job, the ability to adapt to new systems, or fear of redundancy can foster resistance.

Missing Leadership: Effective change requires clear and strong leadership to guide the process, communicate reasons and outcomes, and manage the urgency of change. Without this, resistance can fester.

Change Saturation: Organizations that have undergone multiple change initiatives, especially unsuccessful ones, may experience change fatigue, making employees skeptical about new attempts.

This text doesn’t delve into change management, but the points raised highlight the complexities of implementing change. The following sections will focus on planning and envisioning changes within the scope of Enterprise Architecture (EA), emphasizing on application architecture.

Managed Evolution: A Strategic Approach to Organizational Change

Evolutionary Change in Enterprise Architecture Management

In the realm of Enterprise Architecture Management (EAM), we embrace a principle known as Managed Evolution. This concept underscores the reality that transforming an enterprise’s architecture (EA) is a marathon, not a sprint. Here’s a breakdown of what this entails:

- Timeframe: Transforming EA spans years, not just a single project.

- Objectives: Start with a clear vision of desired changes and outcomes.

- Guiding Vision: Establish a vision that acts as a beacon, not a precise blueprint, to align efforts towards an optimal EA state.

Analyzing Current Architecture and Planning Iterative Changes

Let’s dissect the current architecture as of 2018, and consider how to pivot towards our vision:

- Incremental Changes: Make small, manageable modifications rather than overhauling the entire organization at once.

- Planning: Chart out the first steps in detail, including anticipating future changes, focusing on the application landscape for the upcoming planning period.

Balancing Business Value and Architectural Quality

Post each iteration, we must evaluate the outcomes and set plans for the next cycle, always keeping the vision in check. We balance two key drivers:

- Architectural Quality: Governed by principles and criteria that assess the architecture’s quality.

- Business Value: Adapting to deliver tangible value, such as new software applications or enhanced customer relationships.

The Pitfalls of Uncontrolled Growth and Overemphasis on Architecture

An uncontrolled approach can lead to a chaotic EA, resembling the iceberg that sank the Titanic—costly and unmanageable. Conversely, obsessing over architectural purity can lead to a perfect but commercially unsuccessful structure.

A Balanced Corridor of Change

We aim for a middle ground:

- Concrete Objectives: Set realistic goals for each year, balancing improvements in architectural quality with business value.

Iteration Examples

Consider the following progression:

- 2019: Focus on architectural improvement with minimal business value addition.

- 2020: A shift towards adding business value while slightly enhancing architectural quality.

- 2021 and Beyond: Quality takes precedence again, but detailed plans for the distant future remain flexible.

The Dynamic Nature of the Vision and Architecture

The vision provides direction, but the end-state architecture may evolve due to market and internal changes. Therefore, managed evolution stresses:

- Iterative EA changes aiming for a future state.

- Each iteration finds equilibrium between enhancing business value and architecture quality.

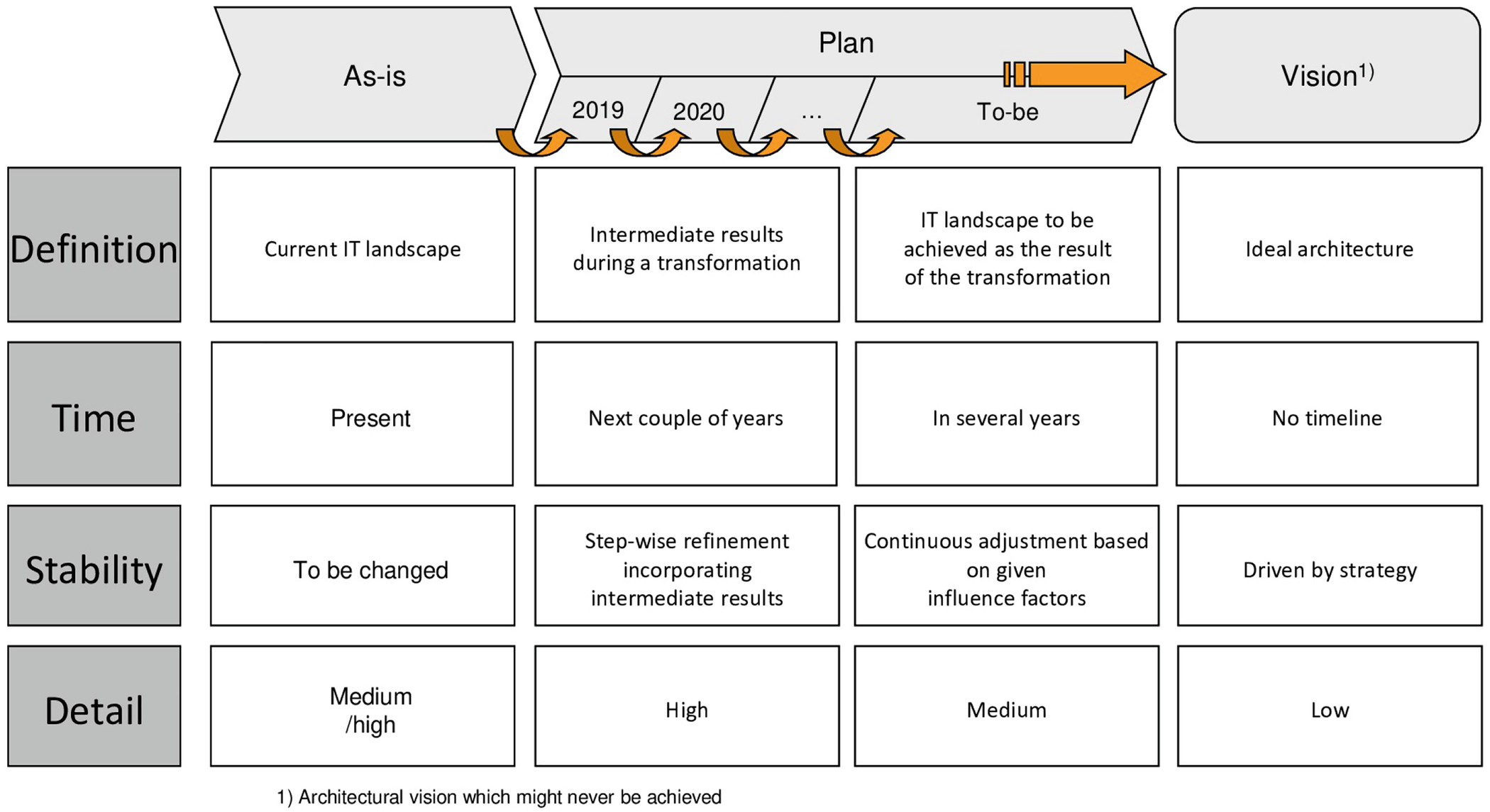

Planning and Flexibility in Transformation

Transformation demands meticulous planning and adaptability. Consider the following aspects of different transformation phases:

- Definition: The scope of each phase.

- Time: The envisioned timeline.

- Stability: The architecture’s stability during each phase.

- Detail: The required detail level for planning.

Detail Levels Across Phases

- As-Is Analysis: High-level understanding with medium to high detail.

- Planning: High detail for immediate next steps, less for future iterations.

- Vision: Low detail, more of a motivational narrative.

Incorporating Strategy into the Vision

The vision reflects corporate and IT strategies, adapting to new business models and market changes, yet remains flexible for unforeseen shifts over a 10 to 15-year horizon.

In summary, Managed Evolution is a strategic and methodical approach to EA transformation, balancing the need for quality and business value while remaining agile enough to adapt to the ever-changing business landscape.

Application Roadmap Management

Overview of Changes in Enterprise Architecture (EA)

In this section, we delve into the dynamics of EA modifications, building on a previously discussed example of transformation through managed evolution. Enterprise architects employ a variety of mapping tools, among which the application roadmap is a pivotal instrument. This document illustrates all modifications in the application environment due to various initiatives. It’s important to acknowledge that Enterprise Architecture Management (EAM) also encompasses business alterations like process and organizational restructuring, which fall outside the scope of this discussion.

Defining the Application Roadmap

An Application Roadmap is a strategic chart that illustrates upcoming adjustments within an organization’s application framework. It specifically targets change initiatives that impact applications. Each initiative is characterized by:

- A defined commencement and conclusion timeline.

- An objective that might involve the deployment of a new application, the alteration of an existing one, or the sunsetting of outdated software.

Initiatives and Their Impacts

The application roadmap provides a snapshot of planned changes, focusing on the efforts that bring about these changes, such as projects or programs. These initiatives could entail:

- Introducing a New Application: This often results in a substantial project that could involve either creating a custom application or procuring and configuring an off-the-shelf solution.

- Updating an Existing Application: Changes can range from minor tweaks to major overhauls, and might include:

- Adding features to meet new requirements.

- Modifying existing functionality to meet revised criteria.

- Expanding the application’s reach to additional organizational units.

- Scaling back on the application’s features.

- Decommissioning an Application: Whether partial or complete, this process needs careful planning due to the implications for users and interconnected systems.

Considerations for Decommissioning

Retiring applications is a common yet complex process, as it involves costs and necessitates the transfer of business value to more effective solutions. Decommissioning must be meticulously planned to avoid disrupting dependent applications and business processes.

Long-term Change Management

Reconfiguring corporate structures is a time-intensive endeavor, particularly when it involves decommissioning applications, which must be managed as formal projects.

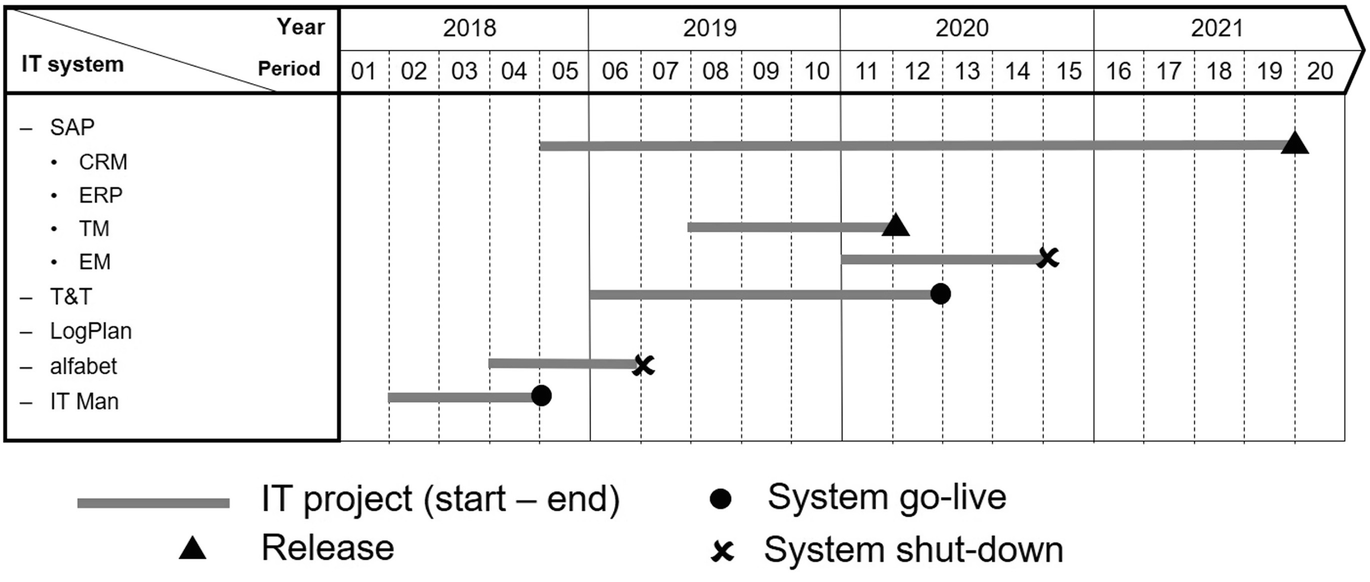

Deciphering the Example Roadmap

In this illustrative roadmap:

- A multi-year project commences in 2018, culminating in a new CRM release.

- Shorter initiatives target other applications like transportation management for updates.

- Redundancies like the event management application are identified for decommissioning, with the transition to T&T.

- A planned overlap exists between the phasing out of alfabet and the adoption of IT Man to prevent operational gaps.

Enhanced Roadmap Details

For comprehensive planning, roadmaps can be augmented with:

- Project milestones and stages.

- Resource and budgetary requirements.

- Contacts for project coordination.

- Application interdependencies.

- Impacted business capabilities or processes.

Integration and Updates

The application roadmap not only reflects changes in the application landscape but also aligns with other architectural views and serves as a conduit to project or program management. It must be regularly updated to reflect any shifts in project timelines.